Books 2022

It’s hard to review all books, but here is a selection of the best books i read in 2022.

Buying this book was an accident.

I misread the name. I thought I was buying a book of poetry by Dorothy Parker!

Imagine my surprise when I took it out of the bag and realised I’d bought a book by an Australian poet, Dorothy Porter.

I wanted to read some poetry so dived into it.

To my great surprise, it was not a collection of poems.

It is unlike any other poetry collection I’ve ever seen.

There is a missing person, a tough lesbian PI, a murder, an irresistible lover and the most glorious erotic scenes you’ve ever read.

It is utterly fascinating.

I did not think I would ever say this about a book of poems: it is unputdownable!

The best accident that ever happened to me.

‘Memory’s truth, because memory has its own special kind. It selects, eliminates, alters, exaggerates, minimizes, glorifies, and vilifies also; but in the end it creates its own reality, its heterogeneous but usually coherent version of events; and no sane human being ever trusts someone else's version more than his own.’

What could I say about this book that hasn’t already been said?

Nothing, really, except, yes, thank you to all my friends for talking so much and so often about it that I had no choice but to read.

It has not been named the ‘Booker of all the Bookers’ for no reason.

If you are one of the few who is not familiar with it, here is a synopsis (God help me!) with a few of my favourite quotes:

The book opens with Saleem Sinai, the narrator explaining that he was born on midnight, August 15, 1947, at the exact moment India gained its independence from British rule. But to tell his (India’s?) story, he goes back 31 years to Kashmir where his maternal grandfather is from.

Except that it is not his grandfather. A love-sick midwife swapped the only two boys to be born at midnight.

I won’t reveal more, and, truthfully, I believe, that it beyond me to summarise the plot as it develops on several levels and plains.

It is impossible to read it as a straightforward narrative as magical and historical elements are intertwined. Every character is ‘real’ but also functions as an allegory, and every event has symbolic, historical and plot development significance.

Now nearing his thirty-first birthday, Saleem believes that his body is beginning to crack and fall apart. Fearing that his death is imminent, he grows anxious to tell his life story. Padma, his loyal and loving companion, serves as his patient, often skeptical audience.

‘Who what am I? My answer: I am the sum total of everything that went before me, of all I have been seen done, of everything done-to-me. I am everyone everything whose being-in-the-world affected was affected by mine. I am anything that happens after I've gone which would not have happened if I had not come. Nor am I particularly exceptional in this matter; each "I", everyone of the now-six-hundred-million-plus of us, contains a similar multitude. I repeat for the last time: to understand me, you'll have to swallow a world.’

‘Picture Singh and the magicians were people whose hold on reality was absolute; they gripped it so powerfully that they could bend it every which way in the service of their arts, but they never forgot what it was.’

This is an extraordinary memoir that is also written in an extraordinary way.

It reads like a novel but is actually the life story of Deborah Feldman who grew up in the Hasidic community in Brooklyn.

Hasidism is an ultra-orthodox form of Judaism. They follow a set of strict rules, including social seclusion, based on the preachings of their founder.

Feldman skilfully shows the practises, rituals and beliefs without preaching. She shows how they affect an individual, particularly a curious spirit like herself. Any deviations, particularly for a woman, are not tolerated and are punished severely.

Feldman is one of few who has left the religious group without major repercussions. She managed to escape with her son (most people cannot take their children with them and thus very often return to the community).

It is one of the most interesting well-written memoirs that I have read.

The Netflix series is inspired by the memoir but it is not an adaptation of it.

I would strongly recommend both.

‘For the original transgression of this land was not slavery. It was greed, and it could not be contained. More white men would come and begin to covet. And they would drag along the Africans they had enslaved. The white men would sow their misery among those who shook their chains. These white men would whip and work and demean these Africans. They would sell their children and split up families. And these white men … who had been oppressed in their own land by their own king, forgot the misery that they had left behind, the poverty, the uncertainty. And they resurrected this misery and passed it on to the Africans.’

Epic, sweeping, and at almost 800 pages, it is a whopper, but never boring.

At the centre of the book is Ailey Pearl Garfield, whose ancestors include Black, White and Creek people. She tells her story starting with her earliest memories, with one major traumatic event early on that will mark her for life.

In parallel, the story of her ancestors is told seemingly by the wind:

‘We are the earth, the land. The tongue that speaks and trips on the names of the dead as it dares to tell these stories of a woman’s line. Her people and her dirt, her trees.’

The two time lines meet towards the end of the book in quite a dramatic fashion.

This is a family history but also the history of the US in many ways. It can be confronting and difficult to read at times but it will not leave you until you’re finished. Even then, little scenes and observations will stay with you. It brought back to me the purpose of history: it is nothing if it doesn’t teach you about the present. And how we repeat it in the present.

This is historical fiction only in the broadest sense of the word as it uses a historical figure (Marie de France) as an inspiration rather than filling in the blanks. (But who knows what her life really was like)

Marie is the illegitimate child of a French noble and, after her mother’s death, she is banned from her estate, to the English court. There, she is deemed too ugly, too tall, and is again banned to an impoverished abbey as prioress.

After she’s recovered from her shock of not being wanted and having to live in almost abject poverty, she takes action as the prioress position entitles her to do. She builds a prospering safe haven for women of all ranks and talents. It is a paradise men do not have access to.

This doesn’t sound like an interesting plot but Groff makes it into one.

I don’t care how far-fetched it is, I choose to believe that it was possible and that there really was such a place. It’s just that women could not tell the stories before.

As a bonus: Lauren Groff’s writing is so beautiful, I’d read anything she’s written.

‘Aging is a constant loss; all the things considered essential in youth prove with time that they are not. Skins are shed, and left at the roadside for the new young to pick up and carry on.’

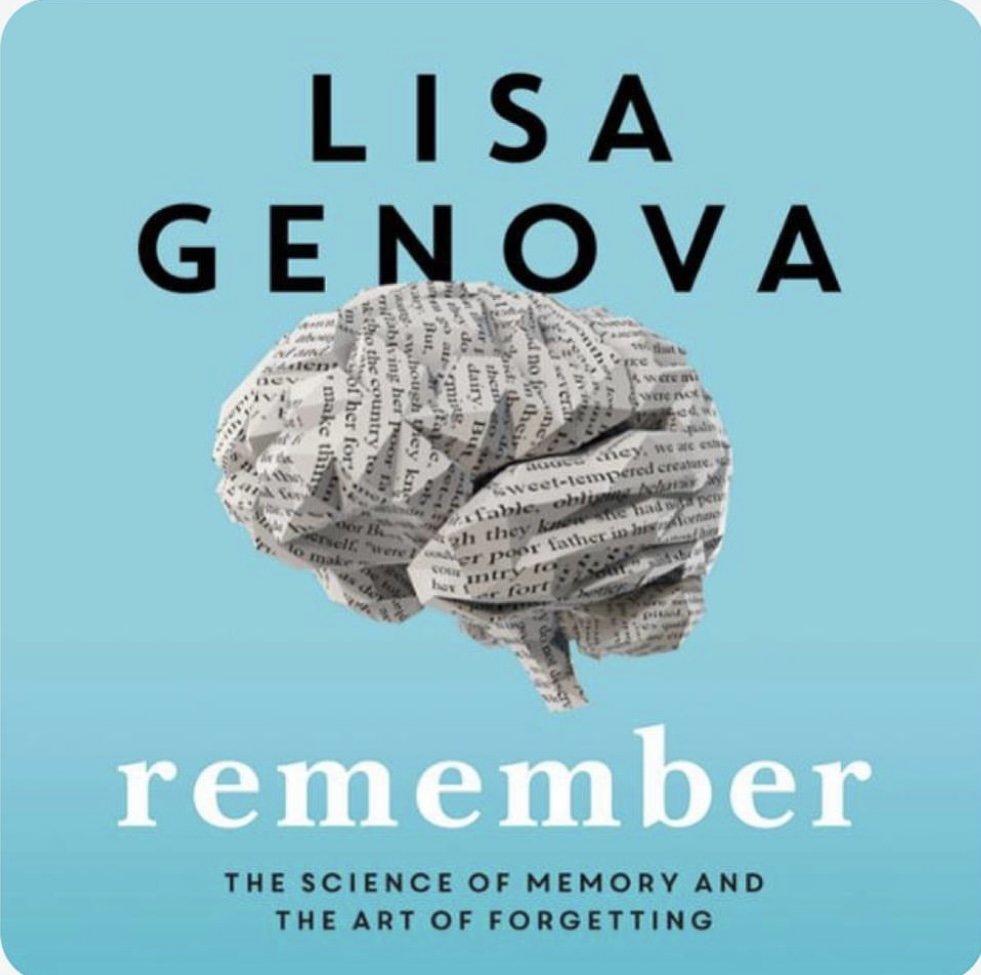

It was only fair that Lisa Genova wrote this book. She scared me to death with Still Alice.

I’ve been looking over my shoulder ever since, interpreting every lapse of memory as Alzheimer’s striking me down.

Her lovely mix of science-y explanations (this is a reflection of my inexperience talking about science; no reflection on the book) combined with ample examples managed to calm me down, even give me some pointers what to do to reduce the chances of Alzheimer’s striking me down.

Thanks, Lisa!

A Mercy is set in colonial America in the late 17th century when slavery is still in its infancy. Jacob is a European farmer who purchases a wife from an England and grows his household with indentured or enslaved white men, Native American and African women.

Their lives are told in a rich tapestry of interwoven dependency, emotional and physical scars still affecting their lives. They are all hungry for love and attention and negotiate it in different ways.

When the master dies and the mistress is also very ill, their little community is endangered and the youngest member, Florens, ‘with the hands of a slave and the feet of a Portuguese lady,’ needs to go and find the handsome blacksmith, who she is besotted by and who seems to be the only one who can save them.

It is often said that every writer, in essence, tells the same story in every book. For Toni Morrison, that story is the story of the ties between a mother and her child. Quite brilliantly and subversively, she makes it again the centre do this book, too. And the last few pages will hit you emotionally like a sucker punch.

‘Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people. It will keep you cramped and insane your whole life, and it is the main obstacle between you and a shitty first draft. I think perfectionism is based on the obsessive belief that if you run carefully enough, hitting each stepping-stone just right, you won't have to die. The truth is that you will die anyway and that a lot of people who aren't even looking at their feet are going to do a whole lot better than you, and have a lot more fun while they're doing it.’

I found it very hard to pick a quote as I LOVED every single line in this book.

It is part memoir, part an instructional manual for new (or old) writers.

Anne Lamott paints such a vivid picture of her life while, at the same time, allowing us to imagine it could be our life.

It’s part serious (and very deep) and part hilarious, making fun of her own foibles and crisis moments. My favourite combination. If I could choose a style in which to write, this is the one I would choose.

‘It’s funny: I always imagined when I was a kid that adults had some kind of inner toolbox full of shiny tools: the saw of discernment, the hammer of wisdom, the sandpaper of patience. But then when I grew up I found that life handed you these rusty bent old tools – friendships, prayer, conscience, honesty – and said ‘do the best you can with these, they will have to do.’ And mostly, against all odds, they do.’