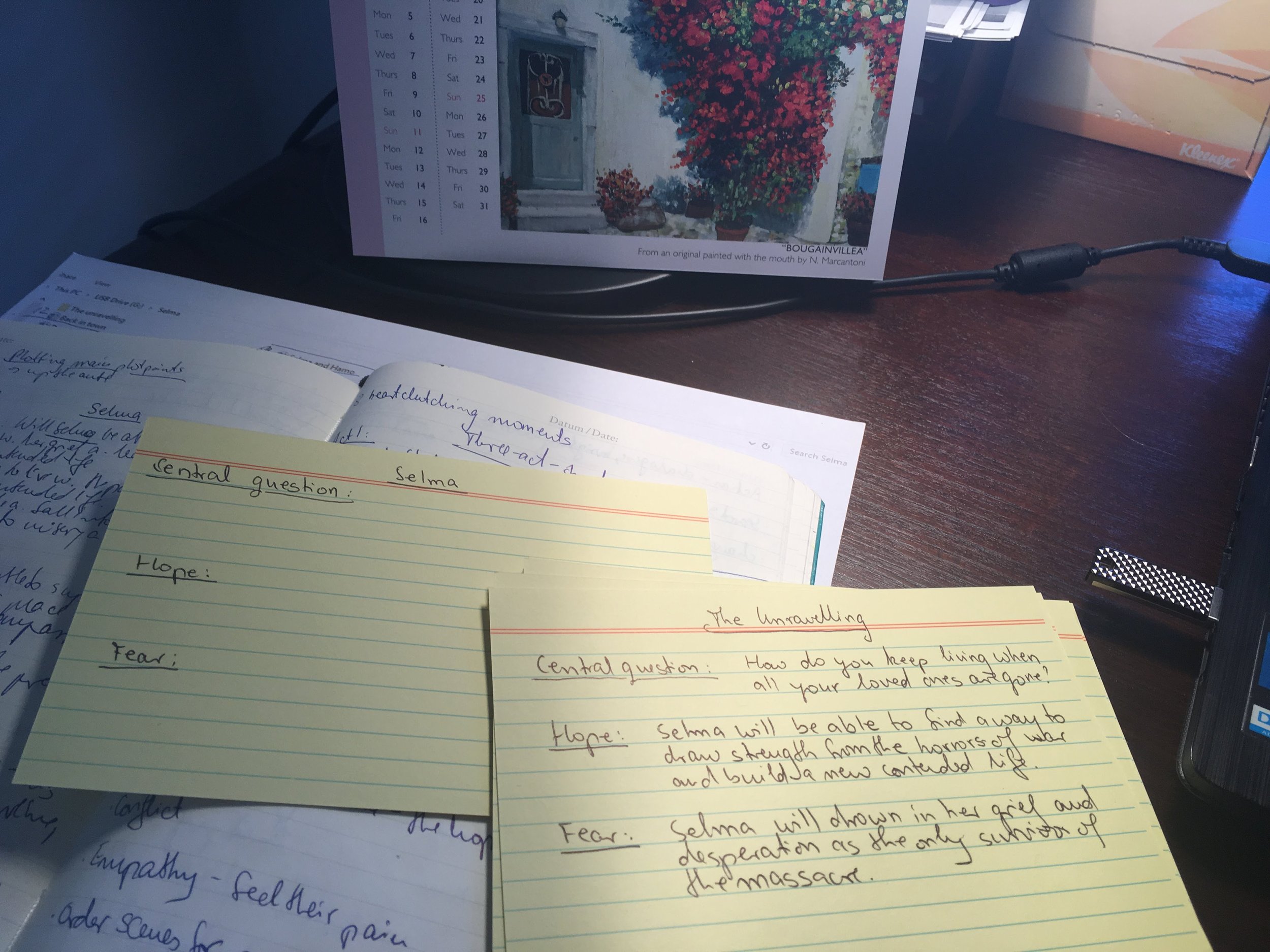

I’m always so excited to get started with a new project. I love exploring whatever conundrum I’ve thought of. And I usually know where it’ll end up. But what do I do between the inception of the idea, the conflict and the end, the resolution?

Enter: The saggy middle.