How to edit your work

There are lots of quotes, guides, manuals that elaborate on the importance of editing. Indeed, it is universally acknowledged that we shouldn’t worry too much about the form when we write our first draft. The form, the paragraphs, the linking, etc, are all things we should focus on later. Still, it can be an overwhelming task when we see just how many things we need to work on. There are many times when I’ve given up because there were just too many things wrong with my writing.

Not any more. I’ve come across this really useful approach that allows me to segment the editing work and focus on one aspect at a time. There are essentially four aspects, and we should never focus on more than one at any given time. It’s like peeling an onion. You cannot get to the heart until you have peeled away all the outer layers.

Developmental Editing

This foundational level focuses on the manuscript's overall effectiveness, addressing three key pillars: character development, structure and plot, and pacing. Structural editing ensures scenes are arranged effectively to heighten tension and keep readers engaged. Plot editing focuses on character motivation and action, ensuring transformations and engaging twists. Pacing adjustments involve cutting sections that slow the story and refining areas that move too quickly, helping maintain reader engagement.

Line Editing

The second level examines writing at the sentence and paragraph level to enhance clarity and flow. This stage refines transitions, sentence structure, rhythm, tense consistency and eliminates clichés. Line editing also removes redundancy and strengthens prose by replacing passive voice with active voice, varying sentence lengths, and cutting unnecessary words.

Copyediting

This level corrects grammar, punctuation, spelling and stylistic inconsistencies such as capitalization, hyphenation, and abbreviations. Maintaining consistency is crucial, ensuring uniform spelling, number usage and character details throughout the text. Copyediting adheres to style guides like The Chicago Manual of Style, which is widely used in narrative writing, or the Australian Government Style Manual, widely used in Australia . Fact-checking is also essential, ensuring historical accuracy in language, setting, and cultural references.

Proofreading

The final level is a meticulous review of the manuscript for typos, layout issues, and formatting errors. Proofreading should be done by someone other than the author to catch overlooked mistakes. Unlike other editing stages, proofreading does not involve adding new content but ensures the final version is polished and error-free.

Mastering the four levels of editing transforms a rough draft into a professional manuscript. Writers who follow this structured approach will significantly improve their work, avoiding the pitfalls of premature fine-tuning and ensuring their story is engaging, clear, and well-structured.

How to become a proficient editor

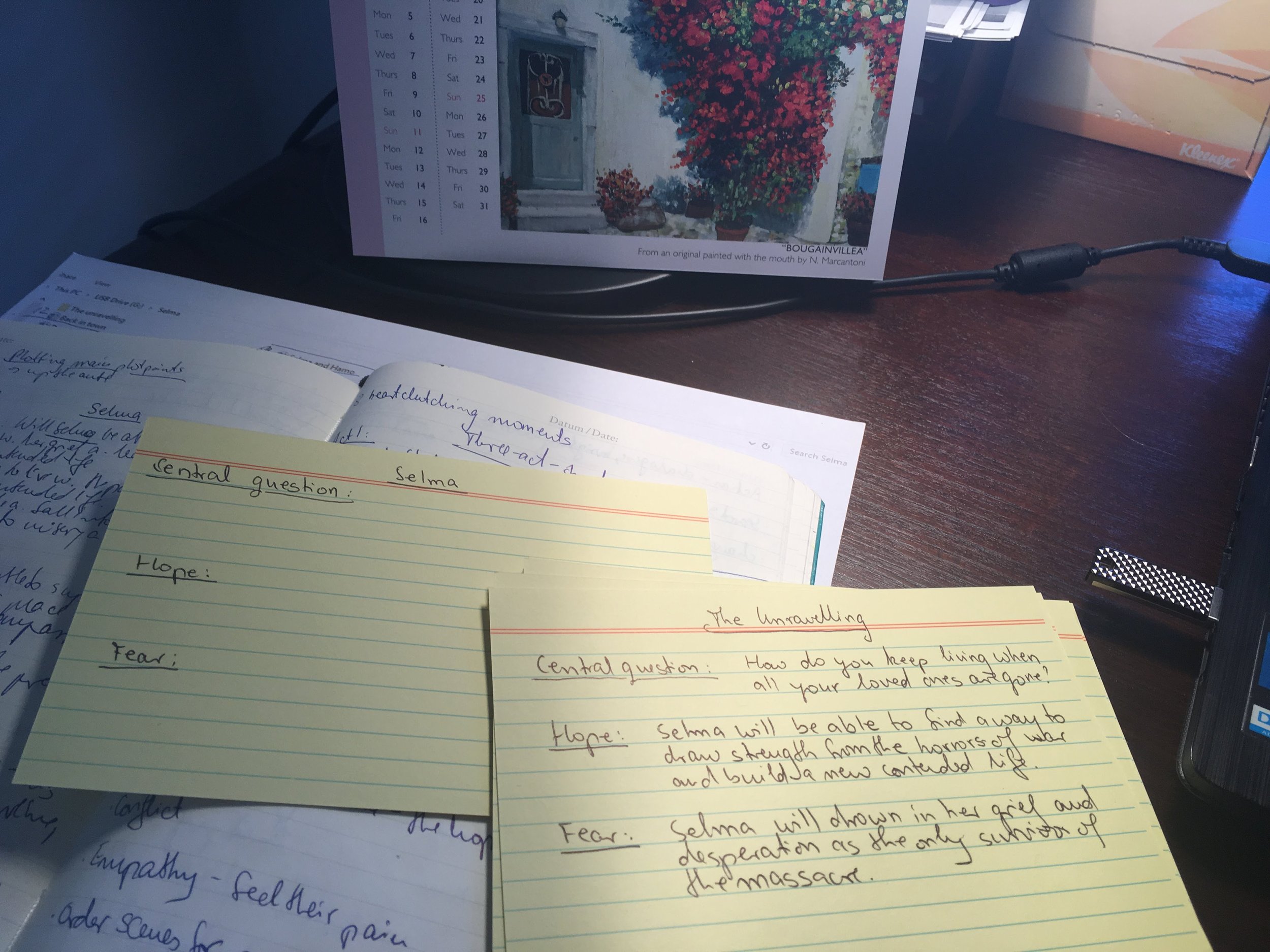

I’d like to repeat again: do not start editing until you have finished your first draft. It will drain your creativity. Pages you may want to change and make perfect may not survive a later edit anyway. But how do you know that you are qualified to do a good edit, on any of the levels mentioned above? Well, without getting a qualification, you’ll probably never know, but there are things you can do/you have probably already done that help you along the way. Here is a list of things that will help with preparing yourself for the editing process:

1. Put your manuscript in the drawer.

It is crucial to gain some distance from your work to be able to switch off being a writer and switch on your editing persona. A month is the minimum amount of time recommended to be away from the manuscript to be able to look at it somewhat objectively.

2. Read, read, read

There is no such thing as ‘wrong reading.’ Any reading is good reading. The best reading is reading widely, reading across genres, including good and bad work. Try and identify what makes you like a piece of work and what doesn’t, how did the writer reel you in or what was off-putting, what threw you out of the story. If you can spot these things in other people’s work, chances are you will sport them in your own as well.

3. Find a writers’ group/writing buddy

These two are not the same and, ideally, you would have both, but the reality is that you may not be able to sustain both. In my experience, writers’ groups are great (I’ve loved everyone I’ve been part of) but more often than not, they dissolve over time. A writers’ group allows you, if nothing else, for a regular timetable in which you need to have work completed. That deadline does wonders! There are many different types of writers’ groups, but the most effective ones are fairly small (five to six people) and the members are at a similar stage on their writing journey. When reading other people’s work, make sure to apply the ‘compliment sandwich’: say something nice about the work, then something that doesn’t work and finish with another nice statement about the work. Be generous with compliments and think twice before finding faults.

A writing buddy serves a similar function to a group but can be more beneficial if you trust each other. With only one person reading your work, you can / should be more specific in what you want from them. They can simply read your work and give general comments, but it may be more useful for you to ask for specifics, eg ‘Is my character’s action logical/believable?’ Also, by looking for specific things in your buddy’s work, you are honing your inner editor, more in tune with your own work.

4. Gain a fresh perspective on your work

Even after a month, you may still be too close to your work to view it with fresh eyes. There are a few techniques that can help you with gaining perspective:

a. Print your work

If you have been working on the screen, print your work.

b. Read aloud

Reading aloud allows you to listen to your story rather than write it. It transmutes you into a reader rather than the writer and makes it easier to spot mistakes and things that just sound wrong.

c. Change appearance of works on screen

This could be trying a different font or size or colour. It tricks your brain into seeing the words in a new way.

d. Set time limits

Limit the time that you spend with your manuscript. I find this works with any type of writing. The fact that my alarm will go off in ten/twenty/thirty minutes focuses me on my writing/editing as nothing else can.

e. Email (not) to a famous writer

Decide to email a chapter to a writer you admire. Get it ready. Type the writer’s email. Before you click on ‘send,’ revise the story one last time. The things you will see are amazing because you are reading with that writer’s eyes not yours. Then, of course, delete the email without ever sending it.

Useful resources:

Australian Government Style Manual

S. Bell: The artful edit

P. Ginna: What editors do: The art, craft & business of book editing

M. McCowan: Effective editing